Grant Saunders asked a series of questions about the quantity of nutrients required in the soil, using calcium as an example. One can see that full discussion here.

When he asked this question, I thought the clearest way to answer it would be with a blog post.

“So if a turf system uses 12 kg/ha per year of calcium, again as an example, (forgive me for metric) would only 12kg/ha present at the start in the soil be sufficient for 12 months growth?”

I’m going to make a long answer out of this, and I’m going to discuss two things. One is pools of nutrients in the soil, and the other is normal amounts of nutrients in the soil.

Soil nutrient pools

Nutrients in the soil can be divided into pools, reflecting the form or status or relative availability of the nutrient. It depends on the nutrient, but for turfgrass soils, it is typical to classify nutrients as soluble, exchangeable, slowly available or non-exchangeable, and solid phase or mineral. Soluble would be those nutrients in soil solution right now, or that would be in soil solution if more water were added to the soil. Exchangeable are those held by cation or anion exchange in the soil. Slowly available isn’t as easily defined; I’d think of that as the initial amount of solid phase material to become available sometime in the future. And the solid phase or mineral matter is the soil itself, specifically the clay, silt, and sand particles that make up the soil.

This summary of nutrient pools from UC Davis explains this in general terms. And this table shows how, for a particular soil, the nutrient pools vary by element.

When doing a soil nutrient analysis, the Mehlich 3 extractant—and most extractants other than water—are extracting all nutrients from the soluble pool and most nutrients from the exchangeable pool. I hesitate to even be that specific. The way I really think of it is that the soil test extractants can be thought of as their own pool. That is, with Mehlich 3, it extracts a pool of nutrients from the soil. And if we test that identical soil again with Mehlich 3, it is going to extract again that same amount of nutrients from the soil. And the same goes for normal ammonium acetate, or Morgan, or 0.01 M CaCl2—use those extractants on the identical soil, and they will extract a pool of nutrients that is specific to the particular extractant.

What do these nutrient pools have to do with the question Grant asked? They have to do with the 12 kg/ha present in the soil. What we are really doing with the soil test is making calculations about a pool of nutrients specific to a particular soil test extractant, and by testing the same soil with the same extractant over time, we then measure changes in quantities of nutrients in that particular pool.

Now to what is normal.

Normal amounts of nutrients in the soil

It’s not enough to make sure there is a quantity (or a pool) of nutrients in the soil, at the start of the season, that is equivalent to the amount the grass will use that season. See the analogy about airplane fuel at the end for more about that.

Normal soils, even low cation exchange capacity (CEC) sands commonly used for turfgrass rootzones, have a normal amount of calcium that is many times more than the grass can use in a season.

What is normal varies by element. And the relation to grass use obviously depends on climate, grass type, and growth rate. To look at what is normal in turfgrass soils, I suggest the SI (sustainability index) app.

Setting 12 kg/ha of Ca into mg/kg (ppm), assuming a rootzone depth of 10 cm and a soil bulk density of 1.5 g/cm3, and I get 8 ppm. If you then set the soil test calcium to 8 ppm in the SI app, the SI goes to 0.00. In the thousands of soil samples from good-performing turf used to calculate the MLSN guidelines, none have Ca that low. It is exceedingly abnormal to have Ca that low and to have good-performing turf.

There is some amount of nutrients that are normal to have in the soil. This is what the MLSN and Global Soil Survey projects have been about—finding what is normal in good-performing turf.

Then if one finds a minimum level—we used 0.1, but there is nothing magic about that particular number—that one is comfortable with, from within that “normal” range, one can make fertilizer calculations to ensure the soil never drops below that minimum.

This approach is based on there being a pool of nutrients that are extracted by a particular extractant. And it is based on ensuring the soil has a normal amount of nutrients.

Now I can answer that question about 12 kg/ha, if that is the annual grass use, being enough (or not) in the soil at the start of the year. In absolute terms, 12 kg/ha is not enough. But if we are considering the pool of Ca extracted by the same soil test extractant at the start and the end of the year, and if we ensure the soil already has a minimum level already present in the soil, and then calculate the difference of 12 kg/ha in that pool from the start of the year to the end, while still remaining above that minimum, then 12 kg/ha is surely enough.

Two related questions

1) “What is the advantage to a higher amount in the soil?”

If we are talking about amounts above some selected minimum, then to the plant, no advantage. To the turfgrass manager, the advantage is simply the luxury of knowing that there is plenty there, and one won’t have to apply that element for some time.

2) What’s the value of soil testing versus applying ratios of nutrients that match turf use in each application as suggested by STERF?

The STERF approach and the MLSN approach will recommend identical amounts of fertilizer if the soil is at the minimum level. But let’s say we have soils with an SI of 0.5. Using the MLSN approach, which requires soil test data to make the calculation, we can omit a lot of nutrients from those applications until the soil levels get closer to an SI of 0.1. Using the STERF approach, all nutrients get applied, no matter how much is already present in the soil.

I predict the turf performance will be the same whether the nutrients are applied or not, so long as the soil remains above a safe minimum. The advantage to soil testing is that one can apply fewer nutrients and get the same turf performance.

This is currently being tested for P in the STERF-funded SUSPHOS project, which you can read about in their 2017 annual report.

Airplane fuel requirements

I thought for a long time about what type of analogy might make this clear. Airplane fuel isn’t a perfect analogy, but some aspects of the calculations are similar.

It would be a big problem if turf would not have enough nutrients. It would be a disaster if an airplane would have insufficient fuel.

Airplanes are not fueled with only the amount of fuel that it takes to get to the destination. There are additional amounts required to ensure that airplanes don’t run out of fuel.

When calculating the fuel quantity for a flight, I found these minimum requirements for commercial flights from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO):

- Taxi fuel plus

- Trip fuel (to reach intended destination) plus

- Contingency fuel (higher of 5% of “trip fuel” or 5 minutes of holding flight) plus

- Destination alternate fuel (to fly a missed and reach an alternate) plus

- Final reserve fuel (45 minutes of holding flight for reciprocating engines, 30 minutes for jets) plus

- Additional fuel (if needed to guarantee ability to reach an alternate with an engine failure or at lower altitude due to a pressurization loss) plus

- Discretionary fuel (if the pilot in command wants it)

With turfgrass, it makes sense to me to have a minimum amount in the soil that never gets touched, that we are confident is enough to produce good turf, and then to make calculations based on changes in the pool of nutrients extracted by a particular soil test extractant.

If you’ve read this far

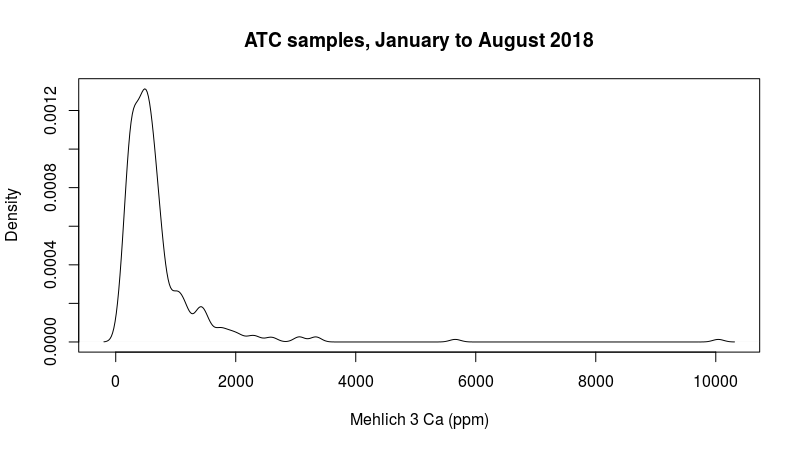

Here are Ca data by the Mehlich 3 extractant for turfgrass soils tested by ATC clients in the past 8 months. Most of the density—that is, most of the samples—is less than 1000.

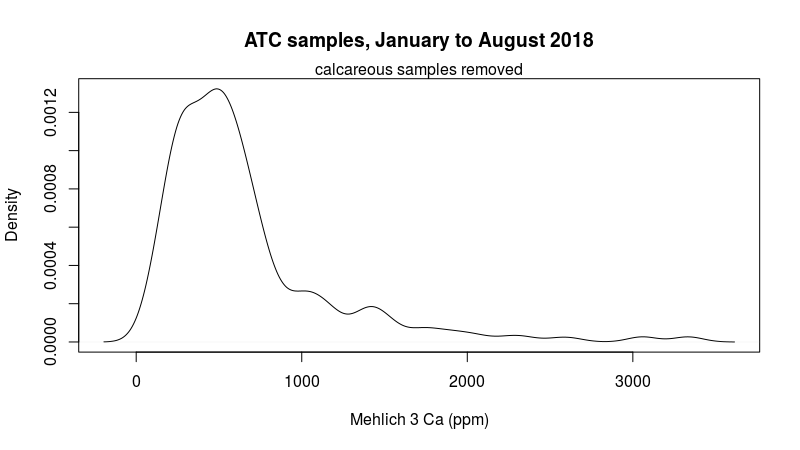

After removing the calcareous samples with higher Ca, it’s apparent that most of the samples are about 200 to 700.

The point I try to show with these plots is that although the grass may use only about 8 ppm or similarly low amounts of Ca in a year, soils naturally have a lot more Ca than that.