Regular readers of this blog will be familar with some previous attempts to estimate the N mineralization in turfgrass soils. There was this from 2010, which I wrote about in 2015 saying “I wouldn’t explain it this way again.”

What I’d done then was estimate a maximum of 4 g N m-2 could be mineralized in a year for each 1% of soil organic matter, and then I tried to spread that mineralization over the hottest 120 days (4 months) of the year, and used the temperature-based growth potential—GP—to adjust for temperature. That was pretty crude, and I figured it must be something like that, but I wanted a better estimate.

For the past few years I’ve been making a more general estimate, still crude, but expressed as an annual amount, based on organic matter being 5% N, and expecting that from 1 to 4% of that N would be mineralized each year. This is straight out of the Soil Fertility and Fertilizers textbook by Havlin et al. I’ve written about that extensively in my monthly ゴルフ場セミナー column, more so than I have on this blog.

In May, I was excited to come across an article that gave a way to make estimates on a shorter time interval. The article is Nitrogen mineralization from soil organic matter: a sequential model by Gilmour and Mauromoustakos. I’d missed this when it was published in 2011. Now, I dropped everything for a few hours and read the paper and worked through the calculations.

The model described by Gilmour and Mauromoustakos is especially useful because it gives an estimate of N mineralization for a time period given temperature, soil water content, and the amount of organic matter in the soil at the start of the specified time period. Calculations of the estimated N mineralization by the Gilmour and Mauromoustakos model for daily or weekly time steps, and then summed for the entire year, were right in the range described by Havlin et al. for the expected annual mineralized amounts.

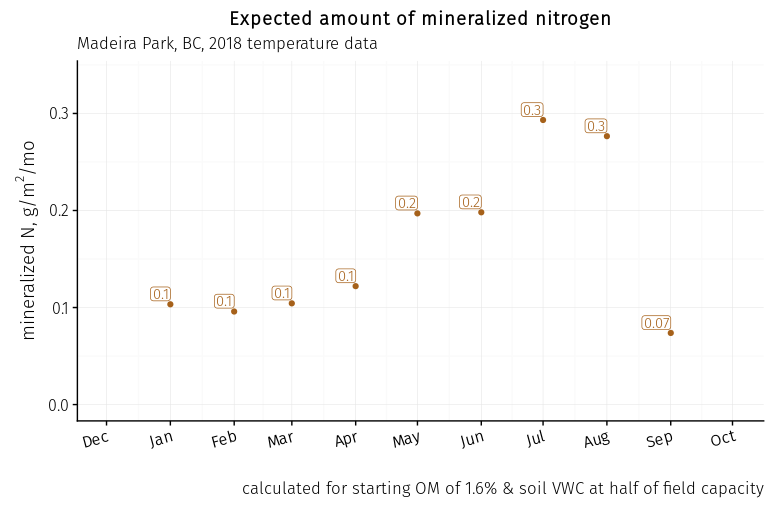

This is really useful for turfgrass management, as a starting point estimate for how much N may be mineralized under certain environmental conditions. One can then adjust maintenance practices and fertilizer inputs accordingly. I’ve put the Gilmour and Mauromoustakos model calculations to use for ATC soil test reports, generating a prediction of N mineralization by month for the 12 months after the soil test, based on the site temperatures, soil water maintained at an average of 50% of field capacity, and the organic matter measured on the soil soil test.

An example of the starting point estimate

Jason Haines wrote a few days ago that “the rains have brought an increased growth rate despite applying almost no fertilizer in the last month.”

As expected the rains have brought an increased growth rate despite applying almost no fertilizer in the last month. pic.twitter.com/9JABpIb0P9

— Jason Haines (@PenderSuper) September 8, 2018

I wondered how this model might make some estimates related to changes in soil moisture content. I got temperature data from the Pender Harbour GC location using the Dark Sky API. Then I estimated N mineralization using equations based on the Gilmour and Mauromoustakos model.

With temperature data through yesterday, assuming the top 10 cm of soil has 1.6% organic matter and the soil water was maintained at 50% of field capacity, this is the expected mineralization: a total of 1.5 g N m-2.

What about the effect of rain? If the soil goes from 50% of field capacity up to 80% of field capacity, expected mineralization using these model equations goes up by 73%. Plus there is the expected increased growth from having more water available to the grass. And there is also flush of mineralization when dried soils are rewetted.

One expects that the growth of the grass would double (or more) from the effect of increased water supply to the grass and with the substantial increase in mineralized N now available to the grass.