A correspondent wrote with this inquiry:

“As discussed a question regarding how soil tests work.

Do the various soil tests only test for readily soluble nutrients in a given soil sample, for example the ions within the capillary stored soil moisture? Or does a soil test give the measurement of the total amount of certain elements within the soil, including elements that are insoluble compounds?

Trying to get my head around this.

If it’s just soluble nutrients then would it be correct to say that a change in ph would give a different test result for certain elements (eg iron at lower ph than 6) despite the fact that there could be the same amount of that element in the soil test, just more shows up in the test because it is more or less soluble at different ph readings.

I wasn’t clear on what the soil test indicates basically, soluble nutrients/plant available forms of elements or a total contained elemental reading for the soil.

Any clarity you could offer would be much appreciated.”

I wrote this long reply:

This probably is easier to make clear in an in-person 15 minute conversation together with a pad of paper or a blackboard to draw a few things out.

I’ll try to explain here and please let me know further questions.

Let’s consider potassium, which is one of the simplest elements in terms of understanding what the soil test number means. I’ve attached an article about this that shows some test results.

So we are going to have a soil, or a range of different soils from all over a country, we will only consider K extracted, and now we will use a variety of soil tests.

By soil test I actually mean “extracting solution”, although other things may vary also such as shaking time and ratio of soil sample to extracting solution.

Soil samples (at left) mixed with a calcium chloride solution and (at right) with a sodium chloride solution, showing the difference in clay flocculation depending on the salt in solution.

Soil samples (at left) mixed with a calcium chloride solution and (at right) with a sodium chloride solution, showing the difference in clay flocculation depending on the salt in solution.

Water as an extractant is only going to return the potassium that is in soil solution or would easily be in soil solution. It gets none of the K on exchange sites in the soil and none of the insoluble K.

Any dilute salt (like 0.01 M CaCl2) is going to get what is in soil solution plus what is on the cation exchange sites. At least in sandy soils, or soils with low CEC, figure that a dilute salt is going to get pretty much all on the exchange sites. In a rich soil with a huge CEC, the amount of salt in the solution won’t be enough to displace all the K on the exchange sites.

Normal ammonium acetate or sodium acetate or other extractants that have a moderate pH and a lot of salt in them are going to, by definition, extract all the K that was on exchange sites and all the K that was in soil solution.

Mehlich 3 and similar extractants will get all that is in solution, plus all from exchange sites, and a tiny fraction of the structural or non-exchangeable K in the soil. That is, they get a tiny bit of the K that is part of the soil particles themselves.

Then there are boiling nitric acid tests, for example, that will get almost all of what is considered non-exchangeable.

And beyond that there is total digestion of the soil and analysis of what it is composed of. That gives the total amount of K in the soil.

Basically it works something like this for every element. K is the easiest (for me at least) to understand, with Mg and Ca being similar in simplicity. P and S and micronutrients and N are more complicated, but basically soil testing works something like described above for all of them.

After you’ve read through the above, you’ll realize that wrapping your head around your own test results must involve some knowledge of what the extractant was. Basically, pH is going to have an effect on water as an extractant and on dilute salts as extractants. The standard test methods tend to be stronger, like ammonium acetate or Mehlich 3. In those, pH isn’t going to affect the results too much.

The typical test results you see are going to represent 100% of what is in soil solution, and they will also represent about 100% of what is on the cation exchange sites. That is what most soil tests, the common ones used for global agriculture, are going to show.

When you get to micronutrients, which have a different chemistry and are not on cation exchange sites, or P, which is not on cation exchange sites, then it isn’t as clear to explain just what the number means.

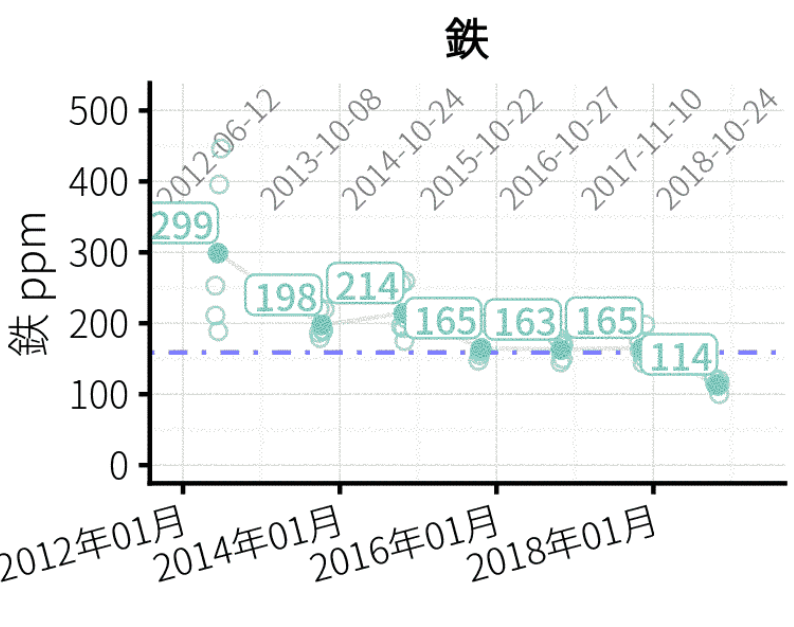

If I have a soil test for iron from the Mehlich 3 extractant, for example, how do I go about interpreting it? I’ve attached a chart of data with Mehlich 3 iron results for one of ATC’s soil testing clients. It’s in Japanese, but if you understand it to be iron from putting greens in ppm over a multi-year period I don’t think the language difference will throw you too much.

I don’t know what 100 or 200 ppm means for Fe, exactly. But I do know:

- the blue horizontal line at about 160 ppm? That line represents the average Fe extracted for every ATC soil sample from putting green soils, excluding this particular course. So that means, for putting green soils, it is normal to have about 160 ppm Fe.

- the time series shows that this course started at an Fe of more than 200 and at the most recent testing had an average of 114. Over the past 7 years, the soil test Fe seems to be going down.

- I would interpret this not as a decision to add or not add Fe; actually one almost never makes a fertilizer recommendation for Fe based on a soil test result. But I provide this information to turf managers and they can quickly see 1) how their samples compare to what is normal for putting green soils in general & 2) how their soil test result is changing over time.

My wish is that the turf industry worldwide would use a standardized extractant. I like 0.01 M SrCl2. Such a test extracts at the pH of the soil so it is easy to interpret. But there is no standard now, and I have no expectation that there will ever be. Thus, we are in the situation now where your simple question gets an answer that is a bit of a non-answer too.

I would also suggest to not read too much into soil tests. pH is important to know. Organic matter is useful to know. P and K can be useful to know in terms of being able to save money and effort by not applying them when you have done a soil test and find there are already ample amounts of those elements in the soil.

For fine turf management, I think of nutrient use as a flux. What is the quantity of nutrients used by the grass on a per area basis for a time duration? That is, how many grams of any element is the grass using per square meter per day, or per month? The amount for golf course turf is pretty small when you calculate it. For football or other sports turf it can be more, maybe 5 to 10 times larger flux most of the time. But this is all still a flux, and one can ignore the soil and ensure that the nutrient supply to the grass is the same (or slightly more) than the flux of nutrient use.

Soil testing for all the elements then becomes useful as a means of reassurance and a means of saving money and effort; the use fluxes are generally quite small, so when one tests the soil, it is common to find that the soil contains more than enough to meet the grass requirements. Thus, soil testing often allows one to skip nutrient applications and save the money and effort involved with those applications, by providing knowledge that the soil contains enough to meet the use flux.