The other day it rained at ATC南店. I knew that the grasses would grow at a faster rate after the rain than they had been growing prior to the rain.

Some grass at ATC南店 after a tropical thunderstorm. I wondered about the subsequent grass growth, and how to partition the cause of that growth between N from the rain, increased N mineralization, or increased soil moisture content.

Some grass at ATC南店 after a tropical thunderstorm. I wondered about the subsequent grass growth, and how to partition the cause of that growth between N from the rain, increased N mineralization, or increased soil moisture content.

But I also wondered about the cause of that future growth. Would there be a substantial amount of nitrogen (N) supplied because of lightning in that storm? Almost certainly not. Would there have been a lot of N in the rain itself? Maybe. That’s something I could check. Would there be a flush of N mineralization from soil organic matter? I could calculate that. Would the growth be from the water itself? Perhaps. I wondered if I could make some calculations to express the probable growth effects on the same scale.

What I’m going to do here is get estimates of three things, and then express those in terms of how much I’d expect them to influence growth. Each of these things have the potential to influence growth after a rain event. These are:

- a) the probable amount of N in a known amount of precipitation

- b) the probable amount of N mineralized after a known amount of precipitation

- c) the probable effect of growth from a known amount of precipitation

I’ll express all of these, eventually, in the same units—as the clipping volume in mL/m2.

a) the probable amount of N in a known amount of precipitation

I’ve written about this before and that post has links to actual data on N deposition. Check that out if you want to find out how much N you may receive from the sky where you are. In general, the N deposition will be less than 2 g N/m2/year (less than 0.4 lbs N/1000 ft2/year).

A brief aside here about lightning and N: the amount of N produced by lightning might be less than you think. The N oxidized by lightning comes to about 0.002 g N/m2/year (0.0004 lbs N/1000 ft2/year). Simpson et al. have a recent discussion of this.

I want to work through a semi-realistic example. Let’s take our location for this example as New Forest Golf Club in England, and consider what might happen on putting green turf.

Teeing off at the New Forest Golf Club.

Teeing off at the New Forest Golf Club.

The UK Air Pollution Information System (APIS) says that total deposition of N at this site is 1.29 g N/m2/year. Normal annual precipitation at nearby Southampton is 780 mm.

Let’s take a precipitation amount of 20 mm. 20 mm is 2.6% of the annual precipitation. If we take that N deposition as coming entirely from rainfall, and spread evenly through the year, then that 20 mm of rain will contain about 2.6% of the annual N deposition—that comes to 0.03 g N/m2 (0.006 lbs N/1000 ft2) delivered to the turf in this 20 mm rain event.

What growth amount do I expect when the grass is supplied with 0.03 g of N? The grass on these greens will have about 40 g N/1000 g dry leaf matter. The 0.03 g of N from the rain will contribute to about 0.75 g dry leaf matter/m2.

To convert that dry matter to clipping volume, I expect that 1 g/m2 of dried putting green clippings (from bentgrass, Poa annua, or bermudagrass) will have a #ClipVol of 16.67 mL/m2. If we have 0.75 g of clippings produced from this N added in the rain, then I expect the increase in clipping volume will be 12.5 mL/m2. I’m going to express this as the average over five days—the five days immediately after the 20 mm rain—so we get an expected increase in growth from N in the rain of 2.5 mL/m2/day.

b) the probable amount of N mineralized after a known amount of precipitation

I’ve written about temperature and soil water content effects on mineralization, too. Using calculations based on the sequential model of Gilmour and Mauromoustakos, we can get an estimate of N mineralization after this 20 mm of rain.

I’m going to consider the mineralization in the top 10 cm (4 inches), make this calculation for a soil with 2% organic matter in that top 10 cm, fix the soil temperature at 20 °C (68 °F) which is reasonable for the New Forest site in July, and assume that the field capacity of the soil is 35% volumetric water content (VWC). I’ll also fix the evapotranspiration (ET) at 4 mm per day.

If, prior to the rain, the top 10 cm of the soil was maintained at a VWC of 15%, then the 20 mm of rain will take the soil right to field capacity. Prior to the rain, the soil was being maintained at 43% of field capacity (15/35). After the 20 mm of rain at the end of day 0, and with 4 mm ET each day, the soil is expected to be at 35% VWC at the start of day 1, then at 31, 27, 23, and 19% VWC on each of the next four days. This comes to an average over the five days of 27% VWC, or 77% of field capacity.

Working through the calculations, with a 10 cm soil depth, 2% soil organic matter, soil temperature of 20 °C, and soil at 77% of field capacity, with soil maintained at 15% VWC pre-rain in a soil with field capacity of 35%, the mineralized N over a five day period is expected to be 0.1 g N/m2. Note that this increase in N mineralized from soil organic matter because of the rain produces approximately three times as much N as was supplied by the rain itself.

Working through this expected effect on clipping volume gives an increase, because of the mineralized N, of 8 mL/m2/day over the five post-rain days.

The mineralized N is site specific. For example, if the soil temperature were 30 °C instead of 20, keeping all other variables the same, the mineralized N is expected to be double, at 0.2 g N/m2.

c) the probable effect of growth from a known amount of precipitation

After looking at N supplied from rain, and N supplied from organic matter, and their respective effects on growth, what about the effect of the 20 mm of water itself?

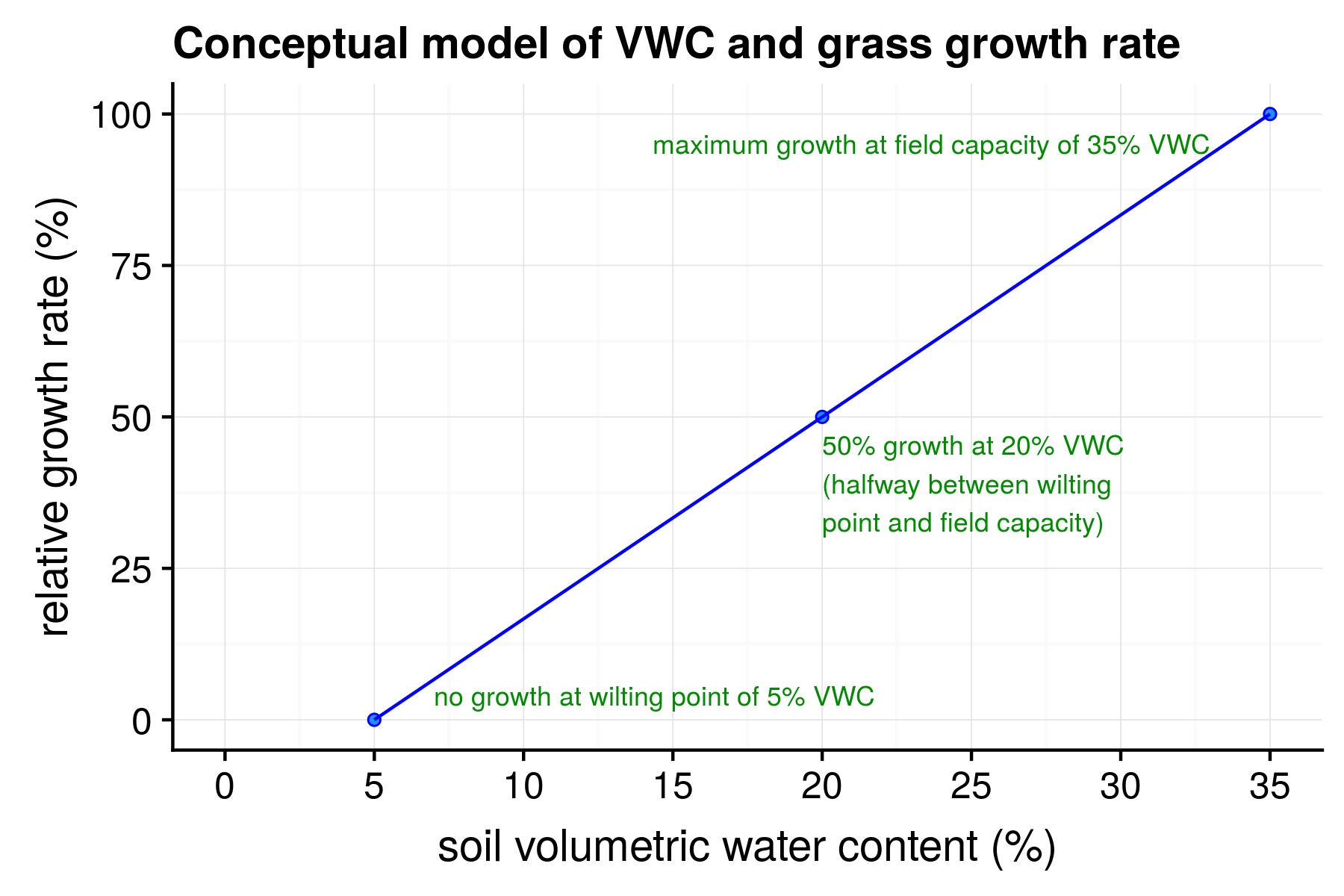

I’m going to assume that there is a linear relationship between soil water content and growth. That is, the growth will be 0 when the soil water content is at the wilting point, and the growth will be at a maximum when the soil water content is at field capacity, and I’ll make a straight line between those two points. This assumption probably isn’t exactly correct—there does seem to be a linear relationship between leaf water potential and leaf growth—but I’m not sure the shape of the relationship between soil water content and leaf water potential.

I’m confident the relative growth rate will be 0 at the wilting point and 100 at field capacity, but the line between those two points may not be straight. For the estimate in this post, I’ve assumed a wilting point of 5% VWC, field capacity of 35% VWC, and a straight line between those points.

I’m confident the relative growth rate will be 0 at the wilting point and 100 at field capacity, but the line between those two points may not be straight. For the estimate in this post, I’ve assumed a wilting point of 5% VWC, field capacity of 35% VWC, and a straight line between those points.

As I described in the previous section, I’m assuming the soil was being maintained at 15% VWC prior to the rain. If there is a linear relationship between VWC and growth rate, then in a soil with a wilting point of 5% and a field capacity of 35%, the VWC of 15% should produce a relative growth rate of 33%. That is, the grass is growing at 33% the rate that it would be at field capacity because of lower water availability.

After a 20 mm rainfall, and with the 4 mm daily ET as described previously, the average soil water content over the next five days will be 27%, which produces a relative growth rate of 73%.

Let’s say the clipping volume pre-rain, when the soil VWC was 15%, was 10 mL/m2/day. If there is a linear relationship between VWC and growth, then this is only 33% of what the growth would be at field capacity. If the soil were refilled to field capacity each day, the clipping volume would be 30 mL/m2/day. After the 20 mm rainfall, I’m predicting that for the site as described here, increasing the average soil water content from 15% to 27% may increase the daily clipping volume to 22 mL/m2/day.

Which has the biggest effect on growth?

I’ve calculated that in the five days immediately following a 20 mm rain event, N in the rain may contribute to increased growth of 2.5 mL/m2/day. The rain will increase mineralization of N from soil organic matter, and that extra N may contribute 8 mL/m2/day. And the direct effect of increasing the water in the soil may contribute 12 mL/m2/day.

These calculations can be modified for your site, based on:

- your soil temperatures

- your soil organic matter

- your wilting point and field capacity

- the amount of rain at your site

- your soil depth

- the amount of N in your rain water

- the evapotranspiration rate at your site

And these predictions can also be checked, by measuring the clipping volume and seeing what happens.

For more discussion of related topics, see: